Motivating That One Child

simple truth:

All children can be motivated; it's our job to find out how.

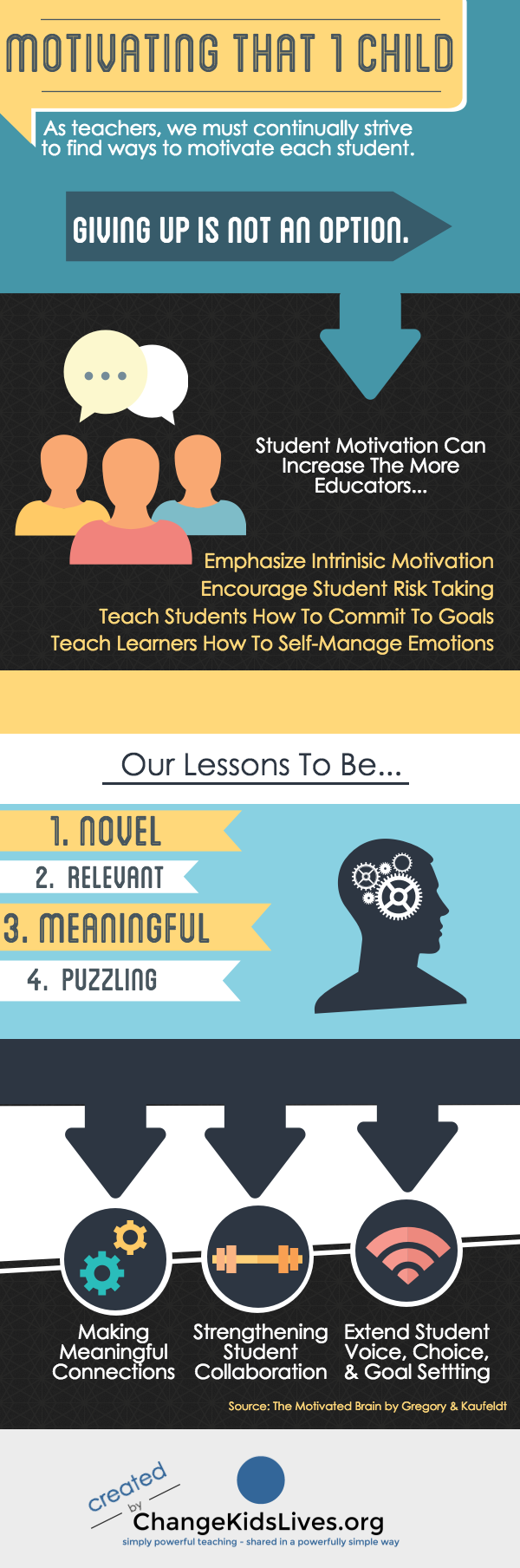

You know that student. Yes, that one. The student, who despite our best intentions and effort, we just can't find what motivates them. And far too often, it seems as though some teachers lose their drive to continually seek new ways to motivate these learners. Yes, some teachers simply quit trying to find new methods to motivate the most difficult students in their class.

It's important for educators to honestly assess a foundational question, do we believe that children can be motivated? Not just most children, rather do we believe that all children can be motivated? For the sake of these learners, I hope that our answer is an emphatic "yes."

research tells us:

Once we affirm this belief, then we need to identify what researchers find that best motivates students. In their book, The Motivated Brain, authors Gregory and Kaugeldt, comment that often teachers use motivation and engagement interchangeably. However, they assert that there's a big difference: a student is engaged if first they are motivated. If student engagement is such a common goal for educators, we must first look at powerful ways to motivate our learners. And motivation is powerful indeed, as Dr. Russell Quaglia, who has spent three decades studying motivation, asserts that students are up to seven times more motivated when they feel like they have a voice in their education.

Below are some research-backed ways that we can motivate even the most difficult students:

try this:

Consider stress and poverty. These two realities for many of our students have a real impact on their young brains. From "fewer academic experiences, to limited vocabulary, verbal skills, and language patterns," it's important that teachers recognize these challenges provide specific opportunities to supplement their learning. Click here for practical strategies for students that support Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs.

Emphasize intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation (genuine interest and sense of accomplishment) often leads to longer lasting positive results as opposed to when teachers use extrinsic motivation (rewards, grades, prizes). Take an inventory of your school culture. Does your classroom management system and how you reward student accomplishments reflect more intrinsic or extrinsic motivation? Adjust accordingly.

Do students find our lessons relevant? While most teachers would say that our lessons are relevant to learners' lives, what would our students say? Continually express to students why this content relates to something they've learned, to their lives, or to the world around them. And then to ensure comprehension, have the students share these connections back using their own words.

Raise students' voice through choice. Do students have choice in their daily academic lives? Start by considering how we can provide them options through content (what they're learning), process (how they're learning the content), product (how they're showing evidence of their learning), or environment (through group/independent work, seated/active learning spaces, and silent/soft background noise).

Teach persistence with goals. Consider teaching social and emotional skills such as self-awareness, self-management, and self-motivation. These attributes are crucial for students to learn how to persist in reaching their short and long term goals. For learn more about social and emotional intelligence, click here to view resources from Casel.org.

review & share this:

For additional reading and referenced research, click here.